AN EVENING WITH HENRY T. GREEN, NOVEMBER 6, 1980

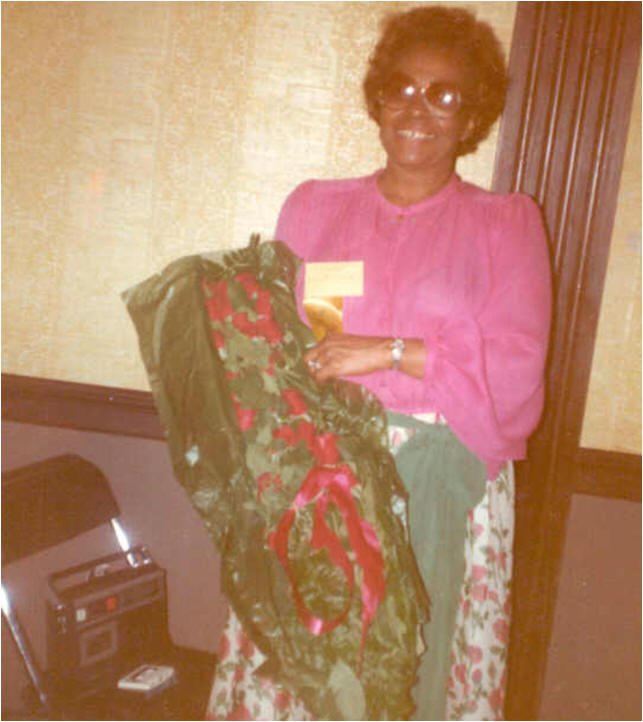

(as written by Ada Elizabeth Webb Clark on May 21, 1984)Ada Webb Clark

On a brisk evening in the fall of 1980, we had what I have come to think of as a most remarkable visit with our cousin, Henry T. Green. We went to his home in Bridgeport, Indiana. Those present were Elsie Lawson Webb, my mother and Henry’s first cousin; Lucian Patton, a cousin; John W. Clark, Sr, my husband (now deceased); and Ada Webb Clark. The conversation was taped by Lucian, and it is hoped that the tape is still in existence. I did take notes and as I began to read what I had jotted down, I am reminded of what an interesting evening it became. When the initials “AEC” appear, it indicates that these are my observations or things that told to me by others. Henry began with this statement, “Before the bugs eat all the leaves off of it, we are here to work on the family tree tonight.” He was referring to the fact that he was advancing in years and that while his mind was most clear, he wished to tell us orally of our family history. I am reminded of the griot from African history who related the history of the tribe to a younger member of the family for the future. All of us who sat spellbound that evening found Henry to be an excellent raconteur. I will try to put my notes and observations down in numerical sequence.

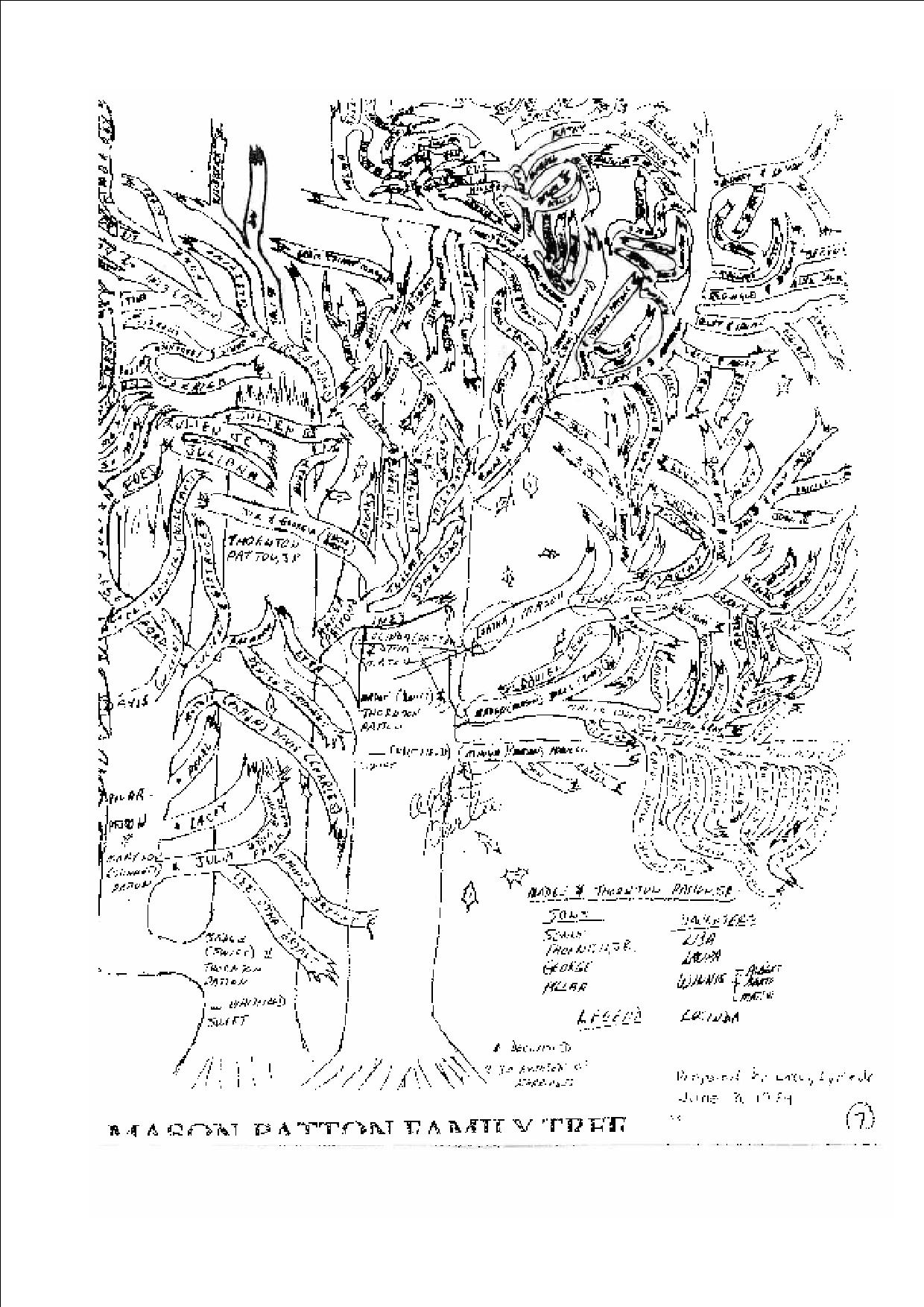

The Early Years The slave names that are part of our family are: Swift, Whitfield, Patton and Mason. These are the grandmothers as he recalls them: 1. Lucinda Mason: Henry’s grandmother (maternal) (my great grandmother), born in the late 1840s or early 1850s. She was born a slave and was freed when she was seven years old. (This was told to me by my grandmother, Leatha Mason. (AEC)) 2. Great, great, great grandmother Whitfield lived in 1804. 3. Great, great grandmother Swift is mentioned. Henry says a turning point in our family was the fact that we were freed in Tennessee rather than Mississippi. It was a matter of economics in that it was more expensive for the slavemaster to take us to Mississippi to free us. He feels that we benefited from this because in Mississippi, we would have become farmers with little or no chance to advance. He said that freedom had nothing to do with servitude but was a matter of economics for the slaveholder.

Lineage

4. Lucinda’s brothers were: Sonny, Thornton, George and Pillar, the baby. Thornton’s wife was called Aunt Kittie. The sisters were Liza, Laura and Winnie. I met and visited Aunt Liza and Uncle Dora as a little girl on a trip to Memphis, Tennessee, with my mother, Elsie, and grandmother, Leatha Mason, and Fannie, my sister, who was a baby in arm. (AEC)

5. Henry speaks of Jomi Swift quite often. I do not know his relationship.

6. The Pattons’ grandmother was a Stinnett. Pillar Patton, Lucian’s father, married a Stinnett.

7. Henry went to Memphis, Tennessee, in 1908, and he says that Memphis was full of our relatives.

8. Lucinda’s sons were: Jim Mason, who was married to Georgia Buddy Mason, who died in 1914 Eddie Mason, who was called Uncle Chippie (died on Labor Day in Indianapolis in the early 1900s)

9. The daughters were: Emma, Leatha (my maternal grandmother), Madge and Etta

10. Emma (Henry’s mother, my great aunt) had a nickname of Emson. When Buddy Mason died, he left a son by his second wife. Emma took this boy and moved to Nashville.

11. Winnie had a daughter named Mattie. She is probably still alive. It is thought that Winnie married and lived in Arkansas. Note: This Mattie is not to be confused with Mattie who was the daughter of Madge and Jim Jones. Mattie Jones Martin resided in Indianapolis. She was the mother of Raymond and Richard Martin.

12. Henry dislikes talking about his natural father, Jim Green. James W. Lytle, his stepfather, was much closer to him than Jim and he had more respect for him. He also respected Gadsen, Aunt Emma’s second husband. I am reminded of this story he told us to compare his feelings for Lytle and Green. “If (James) Lytle, (Jim) Green and Henry (Green) were out on the lake in a boat, and the boat capsized, Henry would attempt to save Lytle and swim to shore. He would assure Green that if he made it and he was not too tired, he would return for him; otherwise ‘So long.’”

13. Uncle George, Lucinda’s baby brother told Henry many things about the early life of the Masons. He was a cobbler (an expert shoemaker). He had a shop in Sercy, Alabama. He had to leave suddenly for he killed a white man in 1908. I remember him. (AEC)

14. In the early 1900s, Henry was on the lecture circuit at many black churches. The Masons Come to Indianapolis

15. The Sims family came off of one of the plantations in the same area as our family. Ned Sims worked at a freight office in Tennessee. He was transferred to Louisville, Kentucky, and later came to Indianapolis and worked at the Big Four Railroad. Word passed around in Sheffield, Alabama, about the opportunities in Indianapolis. Ned sent for his family. Aunt Emma’s family, part of them, came first. Those making the first trip were Aunt Emma, Ross and Theresa (Cousin Sweetie). Later Luther and Henry came. Next came Aunt Madge and Uncle Jim Jones.

16. Lucian and Millard Patton came on a Sunday morning. Henry met them at Union Station. They walked to Hiawatha Street, which was on the west side of town. The address was 420 or 424 Hiawatha. From there, they moved to 1032 Vermont Street.

17. Henry was considered to be a shrewd businessman. He owned quite a bit of real estate on the west side of town. He dealt with the “land folk” from the hospital complex (Indiana University). He was called the “Mayor of the Bottoms.” In the 1940s, there was a song sung by late night people who frequented the streets after hours; it was called “Going to the Bottoms.” Henry owned a store. He often dealt with poor whites from Kentucky upon arrival here until they got on their feet. He said he made his money off them, however.

Miscellaneous Notes Aunt Emma was a very intelligent lady. She read voraciously. In the early days, fraternal organizations were very big among blacks. These groups helped to knit us together. You can compare them to the marches and nonviolent movement of today. They were the salvation of preserving unity among the blacks. (The Grand Lodge was the thing.) A “turning out” day was the largest day celebrated. There were parades, ceremonies, church services and all manner of festivities going on. The blacks were big on wearing resplendent uniforms.

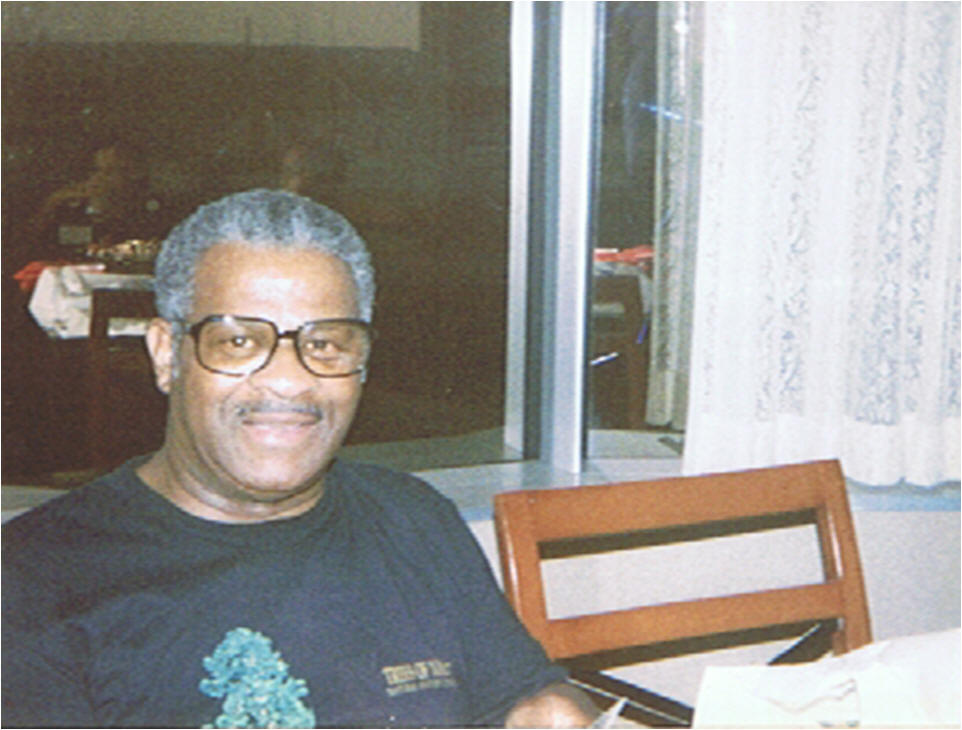

Words to Live By “After you live 80 years, there are a number of things that impede your thoughts and actions.” “I never considered myself better than anyone else.” “I never wanted to live better than anyone else.” “I never wanted to dress better than anyone else.” “Shrouds should have no pockets so there is nothing that you can take with you from this world.” Note: At the time this was written, Henry was 85. His birthday is in June; it is now 1984, and I am told that he does not think he will make it to New York. When we asked him about Chicago in 1980, his reply was, “If the Lord is willing.” If you will recall at our first reunion, one of our aims was that the young people who had not had the honor and privilege of meeting and knowing our older relatives should meet them. Early in 1984, I had a telephone call from my cousin, Lacey Lytle, Sr. He had arrived in town to visit with his one surviving brother, Henry. The day before he left town, both Lacey and Henry spent the evening with me. Lacey told me that he was on to something for the family reunion to be held this year. He left on his way to Washington, DC, to visit the Library of Congress. I remember telling him how well he looked. He said, “Looks are deceiving, my dear.” During the course of the evening, my son, Marc, came in and we sat around the table laughing and talking, and Lacey remarked that he had been in the Marcus Garvey Movement. Marc, who also is a lover of black history, asked if Lacey could stay another day, as he wanted to bring his friends to meet him. The friends did not get to meet him, but spending an evening with both these brothers is an occasion I will not forget. As time goes on, and there are more family gatherings, we will all be made richer for stories that are related about our humble origins. I can remember stories as related to me by my grandmother, Leatha Mason. I would like to put those things down at a later date. You can imagine that hers was an interesting story as she related life on the Mississippi River to me. (AEC) Ada Elizabeth Webb Clark May 21, 1984